| There are 6 labs during this course. For each student, the 5 best performing labs will contribute to your final lab mark. |

- Gain insights into the operation of HTTP

- Get familiar with the basic socket programming

- Preparation for programming assignment

Prerequisites:

- Week 2 Lectures

- Relevant Parts of Chapter 2 of the textbook (Sections 2.2 on HTTP and 2.7 on Socket Programming)

- Basic understanding of Linux. A good resource is here but there are several other resources online

- Several socket programming resources and sample codes for all 3 programming languages are available on this page

- PingServer.java

- http-wireshark-trace-1

- http-wireshark-trace-2

Marks: 10 marks

- This lab comprises a number of exercises. Pl, note that not all the exercises for this lab are marked. You have to submit a report containing answers to selected exercises only.

- Please attend the lab in your allocated lab time slot.

- We expect the students to go through as much of the lab exercises as they can at home and come to the lab for clarifying any doubts in procedure/specifications.

Deadline:

10:00 am Tuesday 05/10/2021 . You can submit as many times as you wish before the deadline. A later submission will override the earlier submission, so make sure you submit the correct file. Do not leave until the last moment to submit, as there may be technical or communications errors and you will not have time to rectify it.

Late Report Submission Penalty:

A late penalty will be applied as follows:

- 1 day after deadline: 20% reduction

- 2 days after deadline: 40% reduction

- 3 or more days late: NOT accepted

Note that the above penalty is applied to your final mark in the report. For example, if you submit your lab report 2 days late and your score on the lab is 8, then your final mark will be 8 - 3.2 (40% penalty) = 4.8.

Submission Instructions:

Submit a PDF document Lab2.pdf with answers to Exercises 3, 4 and 5. Your client should be named PingClient.c or PingClient.java or PingClient.py. Create a tar archive of all the files (e.g. if you have additional header or helper files) called Lab2.tar. Submit the archive using give. You can submit from a lab machine or ssh into the CSE login server. Instructions to ssh into CSE login servers are here . Max file size for submission is 3MB .

IMPORTANT: IF YOU ARE USING PYTHON THEN PLEASE ADD A COMMENT AT THE TOP OF YOUR CODE TO INDICATE THE CORRECT VERSION OF PYTHON (VERSION 2 OR 3). THIS WILL ALLOW US TO USE THIS VERSION OF PYTHON FOR TESTING YOUR CODE.

Original Work Only:

You are strongly encouraged to discuss the questions with other students in your lab. However, each student must submit his or her own work. You may need to refer to the material indicated above (particularly socket programming links) and also conduct your own research to answer the questions.

System Compatibility (Very Important):

We will test your code on CSE machines via the command-line interface. Note that CSE machines support the following: gcc version 8.2, Java 11, Python 2.7 and 3.7. It is thus imperative that you test your code on CSE machines before submitting it. This is particularly important if you write your code on your own machine and use an IDE. You MUST test your code on CSE machines (via command line) before submitting. If we cannot get your code to work on CSE machines, then we can't mark it and unfortunately, you won't receive any marks. This point is also relevant for the assignment.

Exercise 1: Using Telnet to interact with a Web Server (Unmarked, not to be included in the report)

Follow the steps described below. You will notice certain questions as you attempt the exercise. Write down the answers and discuss them with your lab partner to enable him/her to assess your performance. If you have any questions or are experiencing difficulty with executing the lab please consult your tutor.

Step 1: Open an xterm window. Enlarge the size of your xterm window so that it is reasonably large and covers almost the entire screen.

Step 2: Telnet to the vision.ucla.edu web server by typing:

$ telnet vision.ucla.edu 80

Note that the port number for all web servers is “80”.

Step 3: Retrieve the main webpage by typing:

GET / HTTP/1.1

host: www.vision.ucla.edu

Important Note : You will have to press the carriage return twice after typing the last line.

Question 1: What is the content type of the response? What is the size of the response? When was the webpage last modified? Do you see an "Accept-Ranges" header field? What may this be used for?

Step 4: Now execute the HEAD method. When a server receives a request with the HEAD method, it responds with only the message header lines (i.e. the response to the GET method minus the actual requested object).

HEAD / HTTP/1.1

host: www.vision.ucla.edu

Question 2: What is the content type of the response? What is the size of the response?

Question 3: Using telnet, find a way to get the people.html webpage from vision.ucla.edu

Question 4: Why is there the need to include the host in the GET (and HEAD) HTTP 1.1 request messages?

Exercise 2: Understanding Internet Cookies (unmarked, not to be included in the report)

Question 1. Repeat steps 1-3 in the previous experiment for www.google.com.au . Does the site set a cookie in your browser? How can you tell by purely examining the HTTP response message received using telnet? How about www.vision.ucla.edu? Do you think this site will set a cookie in your browser?

Question 2. Open a web browser (Firefox/IceWeasel/Mozilla preferred). Go to the browser preferences and remove all existing cookies. Open the google webpage and then view the cookies. How many cookies are stored on your machine? Which sites installed the cookies?

Question 3. Repeat the above steps for the vision.ucla.edu website. How many cookies are stored on your machine? Which sites installed the cookies? Is the answer inconsistent with the answer for Question 1? Explain why.

Exercise 3: Using Wireshark to understand basic HTTP request/response messages (marked, include in your report)

We will not be running Wireshark on a live network connection (You are strongly encouraged to try this on your own machine. Pointers provided at the end of this exercise). The CSE network administrators do not permit live traffic monitoring for security reasons. Instead, for all our lab exercises we will make use of several trace files, which were collected by running Wireshark by one of the textbook’s authors. For this particular experiment download the following trace file: http-wireshark-trace-1

| NOTE: IT IS NOT POSSIBLE TO RUN WIRESHARK VIA SSH. IT IS A RESOURCE-INTENSIVE PROGRAM AND IT WOULD SLOW DOWN THE CSE LOGIN SERVERS. IF YOU WANT TO WORK REMOTELY, THEN YOU CAN DOWNLOAD AND INSTALL WIRESHARK ON YOUR PERSONAL MACHINE. WIRESHARK IS AVAILABLE ON ALL LAB MACHINES AND IS ALSO AVAILABLE THROUGH VLAB. HOWEVER, IT CANNOT BE INVOKED FROM THE COMMAND LINE. INSTEAD GO TO THE APPLICATION MENU, SELECT "INTERNET" AND "WIRESHARK". |

The following indicates the steps involved:

Step 1: Start Wireshark natively on your machine or through VLAB as noted above.

Step 2: Load the trace file http-wireshark-trace-1 by using the File pull-down menu, choosing Open and selecting the appropriate trace file. This trace file captures a simple request/response interaction between a browser and a web server.

Step 3: You will see a large number of packets in the packet listing window. Since we are currently only interested in HTTP we will filter out all the other packets by typing “http” in lower-case in the Filter field and press Enter. You should now see only HTTP packets in the packet-listing window.

Step 4: Select the first HTTP message in the packet-listing window and observe the data in the packet-header detail window. Recall that since each HTTP message was carried inside a TCP segment, which was carried inside an IP datagram, which was carried within an Ethernet frame, Wireshark displays the Frame, Ethernet, IP, and TCP packet information as well. We want to minimize the amount of non-HTTP data displayed (we’re interested in HTTP here, and will be investigating these other protocols is later labs), so make sure the boxes at the far left of the Frame, Ethernet, IP and TCP information have a right-pointing arrowhead (which means there is hidden, undisplayed information), and the HTTP line has a down-pointing arrowhead (which means that all information about the HTTP message is displayed).

NOTE: Please neglect the HTTP GET and response for favicon.ico, (the third and fourth HTTP messages in the trace file. Most browsers automatically ask the server if the server has a small icon file that should be displayed next to the displayed URL in the browser. We will ignore references to this pesky file in this lab.)

By looking at the information in the HTTP GET and response messages (the first two messages), answer the following questions:

Question 1: What is the status code and phrase returned from the server to the client browser?

Question 2: When was the HTML file that the browser is retrieving last modified at the server? Does the response also contain a DATE header? How are these two fields different?

Question 3: Is the connection established between the browser and the server persistent or non-persistent? How can you infer this?

Question 4: How many bytes of content are being returned to the browser?

Question 5: What is the data contained inside the HTTP response packet?

Note:

Students are strongly encouraged to use Wireshark to

capture real network traffic on their own machines.

Check

https://www.wireshark.org/download.html

for details. Once you have Wireshark installed, do the

following. Clear the cache of your web browser

(Firefox->Tools->Clear Recent History). Launch the

Wireshark tool by typing Wireshark in the command line.

Start Wireshark capture by clicking on: capture ->

interfaces -> click Start on the interface eth0. Run

the Web browser and enter an URL for a website (e.g.

www.bbc.co.uk

). Stop capturing packets when the web page is fully

loaded. Examine the captured trace and answer the

questions as above. This is just for you to try in your

own time. You do not have to include this in your

report.

Exercise 4: Using Wireshark to understand the HTTP CONDITIONAL GET/response interaction (marked, include in your report)

For this particular experiment download the second trace file: http-wireshark-trace-2

The following indicates the steps for this experiment:

Step 1: Start Wireshark by typing Wireshark at the command prompt.

Step 2: Load the trace file http-wireshark-trace-2 by using the File pull-down menu, choosing Open and selecting the appropriate trace file. This trace file captures a request-response between a client browser and web server where the client requests the same file from the server within a span of a few seconds.

Step 3: Filter out all the non-HTTP packets and focus on the HTTP header information in the packet-header detail window.

By looking at the information in the HTTP GET and response messages (the first two messages), answer the following questions:

Question 1: Inspect the contents of the first HTTP GET request from the browser to the server. Do you see an “IF-MODIFIED-SINCE” line in the HTTP GET?

Question 2: Does the response indicate the last time that the requested file was modified?

Question 3: Now inspect the contents of the second HTTP GET request from the browser to the server. Do you see an “IF-MODIFIED-SINCE:” and “IF-NONE-MATCH” lines in the HTTP GET? If so, what information is contained in these header lines?

Question 4: What is the HTTP status code and phrase returned from the server in response to this second HTTP GET? Did the server explicitly return the contents of the file? Explain.

Question 5: What is the value of the Etag field in the

2nd response message and how it is used? Has this value

changed since the 1

st

response message was received?

Exercise 5: Ping Client (marked, submit source code as a separate file, include sample output in the report)

In this exercise, you will study a simple Internet ping server (written in Java), and implement a corresponding client. The functionality provided by these programs is similar to the standard ping programs available in modern operating systems, except that they use UDP rather than Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) to communicate with each other. Note that, we will study ICMP later in the course. (Most programming languages do not provide a straightforward means to interact with ICMP)

The ping protocol allows a client machine to send a packet of data to a remote machine and have the remote machine return the data back to the client unchanged (an action referred to as echoing). Among other uses, the ping protocol allows hosts to determine round-trip times to other machines.

Ping Server (provided)

You are given the complete code for the Ping server: PingServer.java. The server sits in an infinite loop listening for incoming UDP packets. When a packet comes in, the server simply sends the encapsulated data back to the client.

Your task is to write the corresponding Ping client. You can use either C, Java or Python to write your client. You should read through the server code thoroughly, as it will help you with the development of your client program.

Packet Loss & Delay

UDP provides applications with an unreliable transport service, because messages may get lost in the network due to router queue overflows or other reasons. In contrast, TCP provides applications with a reliable transport service and takes care of any lost packets by retransmitting them until they are successfully received. Applications using UDP for communication must therefore implement any reliability they need separately at the application level (each application can implement a different policy, according to its specific needs). Because packet loss is rare or even non-existent in typical campus networks, the server in this lab injects artificial loss to simulate the effects of network packet loss. The server has a parameter LOSS_RATE that specifies the percentage of packets that are lost (i.e. dropped). The server also has another parameter AVERAGE_DELAY that is used to simulate the delay incurred by packets on the Internet. You should set AVERAGE_DELAY to a positive value when testing your client and server on the same machine, or when machines are close by on the network. You can set AVERAGE_DELAY to 0 to find out the true round-trip time between the client and server.

Compiling and Running Server

To compile the server, type the following at the command prompt:

$javac PingServer.java

To run the server, type the following:

$java PingServer port

where the port is the port number the server listens on. Remember that you should pick a port number greater than 1024 because only processes running with root (administrator) privilege can bind to ports less than 1024. If you get a message that the port is in use, try a different port number as the one you chose may be in use.

Note: if you get a class not found error when running the above command, then you may need to tell Java to look in the current directory in order to resolve class references. In this case, the commands will be as follows:

$java -classpath . PingServer port

Your Task: Implementing Ping Client

You should write the client (called PingClient.java or PingClient.c or PingClient.py) such that it sends 15 ping requests to the server. Each message contains a payload of data that includes the keyword PING, a sequence number starting from 3,331, and a timestamp. After sending each packet, the client waits up to 600 ms to receive a reply. If 600 ms goes by without a reply from the server, then the client assumes that its packet or the server's reply packet has been lost in the network.

You should write the client so that it executes with the following command:

$java PingClient host port (for Java)

or

$PingClient host port (for C)

or

$python PingClient.py host port (for Python)

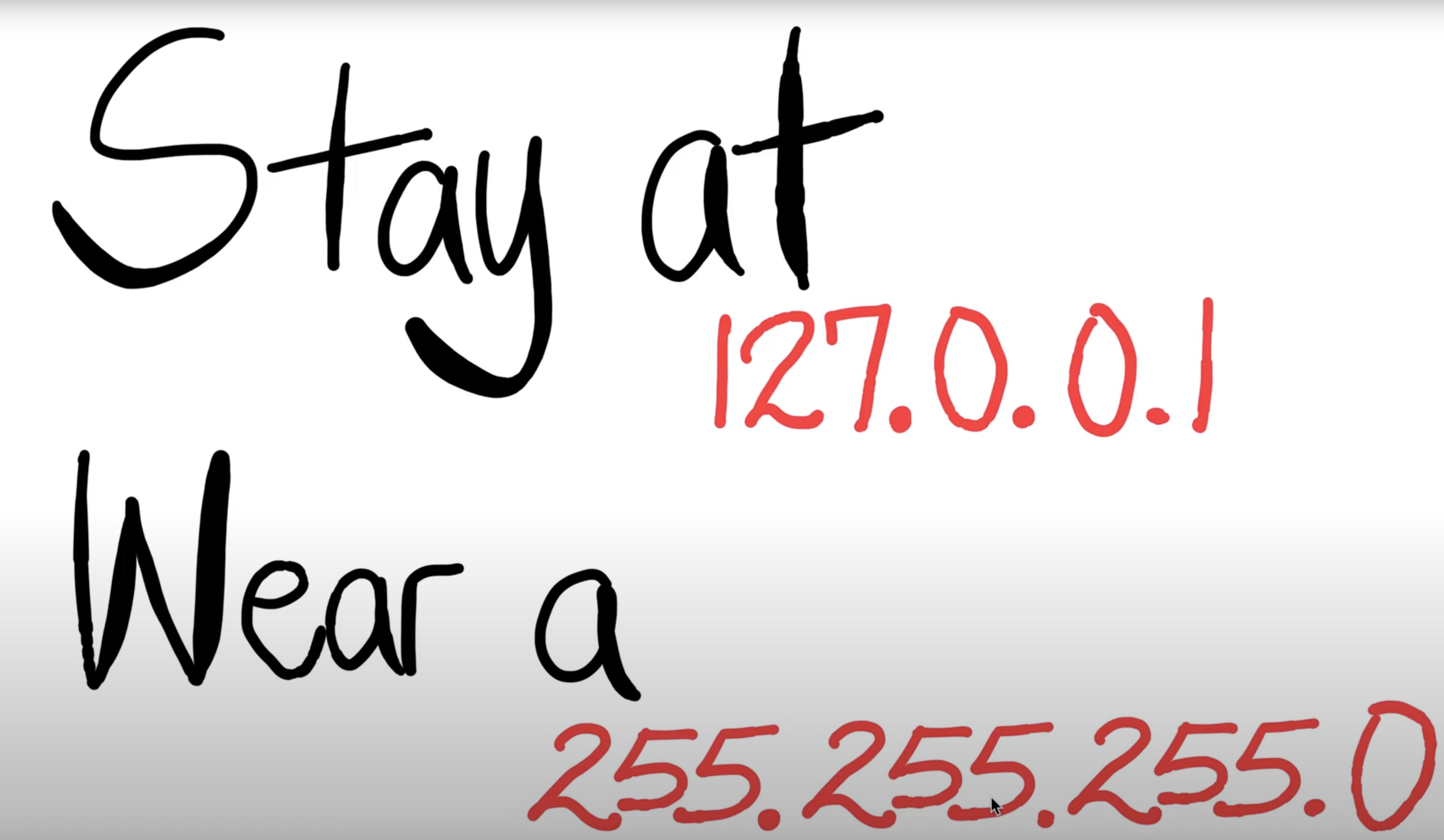

where the

host

is the IP address of the computer the server is running

on and the

port

is the port number it is listening to. In your lab, you

will be running the client and server on the same

machine. So just use 127.0.0.1 (i.e., localhost) for the

host

when running your client. In practice, you can run the

client and server on different machines.

The client should send 15 pings to the server. Because

UDP is an unreliable protocol, some of the packets sent

to the server may be lost, or some of the packets sent

from server to client may be lost. For this reason, the

client cannot wait indefinitely for a reply to a ping

message. You should have the client wait up to 600 ms

for a reply; if no reply is received, then the client

should assume that the packet was lost during

transmission across the network. It is important that

you choose a reasonably large value, which is greater

than the expected RTT (Note that the server artificially

delays the response using the AVERAGE_DELAY parameter).

In order to achieve this your socket will need to be

non-blocking (i.e. it must not just wait indefinitely

for a response from the server). If you are using Java,

you will need to research the API for DatagramSocket to

find out how to set the timeout value on a datagram

socket (Check:

http://java.sun.com/javase/6/docs/api/java/net/Socket.html

). If you are using C, you can find information here:

http://www.beej.us

. Note that, the

fcntl()

function is the simplest way to achieve this.

Note that, your client should not send all 15 ping messages back-to-back, but rather sequentially. The client should send one ping and then wait for either for the reply from the server or a timeout before transmitting the next ping. Upon receiving a reply from the server, your client should compute the RTT, i.e. the difference between when the packet was sent and the reply was received. There are functions in Java Python and C that will allow you to read the system time in milliseconds. The RTT value should be printed to the standard output (similar to the output printed by ping; have a look at the output of ping for yourself). An example output could be:

ping to 127.0.0.1, seq = 1, rtt = 120 ms

We prefer that you show the timeout requests in the output. Only replace the 'rtt=120ms' in the above example with 'time out'. You will also need to report the minimum, maximum and the average RTTs of all packets received successfully at the end of your program's output.

Message Format

The ping messages in this lab are formatted in a simple way. Each message contains a sequence of characters terminated by a carriage return (CR) character (\r) and a line feed (LF) character (\n). The message contains the following string:

PING sequence_number time CRLF

where sequence_number starts at 3,331 and progresses to 3,345 for each successive ping message sent by the client, time is the time when the client sent the message, and CRLF represents the carriage return and line feed characters that terminate the line.

Hint: Cut and paste PingServer, rename the code PingClient, and then modify the code, if you are using Java.

Optional Extensions (For students keen to take up a challenge. THESE ARE NOT MARKED)

When you are finished writing the client, you may wish to try one of the following exercises:

1) The basic program sends a new ping immediately when

it receives a reply. Modify the program so that it sends

exactly 1 ping per second, similar to how the standard

ping program works (difficult).

2) Develop two new classes ReliableUdpSender and ReliableUdpReceiver , which are used to send and receive data reliably over UDP. To do this, you will need to devise a protocol (such as TCP) in which the recipient of data sends acknowledgements back to the sender to indicate that the data has arrived. You can simplify the problem by only providing one-way transport of application data from sender to recipient. Because your experiments may be in a network environment with little or no loss of IP packets, you should simulate packet loss (difficult).

Resource created 4 years ago, last modified 4 years ago.

give cs3331 Lab2 file1 file2 file3 ...

Submitting...

3331 classrun -check Lab2

Fetching...

3331 classrun -collect Lab2